- Realase date: TBD

- Executive Producer: Jiang Ping And Kim Richards

- Produced by: Peter Liapis and William Summers

- Language: English, Chinese

- Review Ratings: Click here

Story

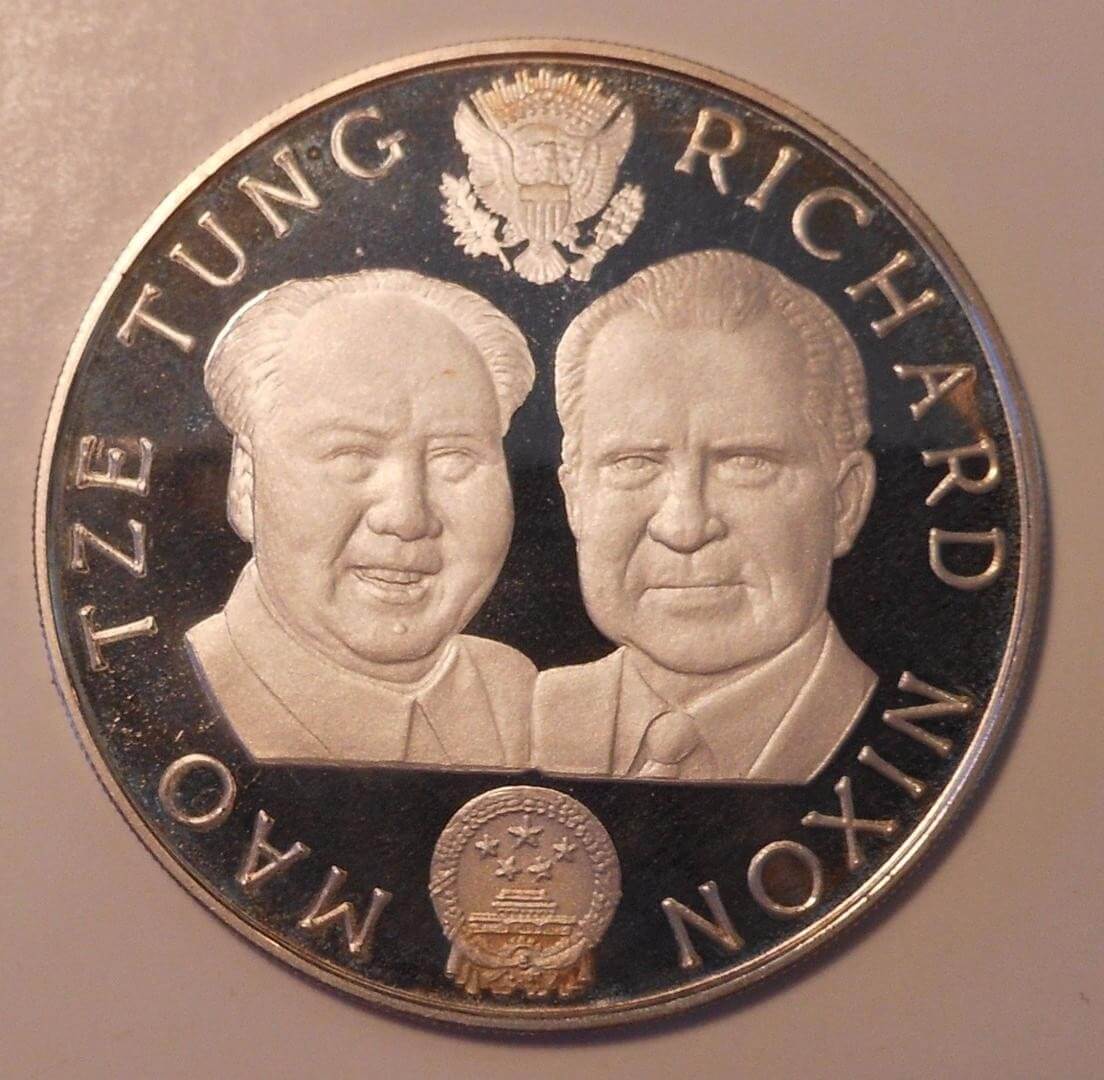

MAO / NIXON

On Monday, February 21, 1972, President Richard M. Nixon arrived in Beijing, China, in Air Force One, the presidential jet. He was greeted only by occupants of an unmarked vehicle and no crowd. Nixon was informed that he would be at his first meeting with Premier Zhou En Lai in just three hours. It was customary at the time to quickly get important figures to their meetings so that nothing could interfere with diplomatic proceedings.

Background

China was not recognized as a sovereign nation until after World War II. Since the 1950s, Richard Nixon had been a staunch anti-communist. The dogma, especially among such right-wing Republicans as Nixon, was that communism was a monolith. There was somebody at a control panel in Moscow who pressed buttons, and communists all over the world responded. However, by the time he became president in January 1969, Nixon’s thinking had changed. In the increasingly dangerous atmosphere of the Cold War, Nixon wanted to bring the Soviet Union to the bargaining table. And he

worried that China -the most populous nation on earth -was living in “angry isolation.” In Nixon’s inaugural address, he said, “The greatest honor history can bestow is the title of peace maker. This honor now beckons America.”

Nixon received intelligence that there was a growing split between the Russians and the Chinese, which he intended to use as a lever. In March 1969, a border dispute between China and the Soviet Union came close to sparking full-scale war. That conflict gave Nixon the opportunity to begin his China game.

Nixon Initiates The Game

In January 1969, a week into his presidency, Nixon called his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, into his office. The president stipulated that, among other projects for the National Security Council (NSC) staff to consider, he wanted China given high priority. General Alexander Haig, Kissinger’s military advisor, recalled him remarking as he left the Oval Office, “AI, this fellow Nixon wants to open relations with China; adding, “I think he has lost control of his senses.” So began two years of preparations toward the era of detente.

The shock inside the White House was understandable. China had been isolated since

1949, when the communist Mao Zedong took control, and the U.S. cut diplomatic ties. In the 1960s, America’s perception was Mao’s brutal Cultural Revolution crushed all but his hardline supporters. China called President Nixon “a gangster.” who wielded “a blood-dripping butcher’s knife:· In 1969, the chances for any relationship between the United States and China seemed slim. Nixon had conceived an elaborate secret plan that would shock America’s allies and alter the global balance of power. It was one of the most stunning surprises of the Cold War-the pivotal move in a game that changed the world. Nixon had stated, “We can see that China is the basic cause of all of our troubles in Asia. If China had not gone communist, we would not have had a war in Korea. It China were not communist, there would be no [Vietnam] war in Indochina.

Secret Communications

The president proposed to make contact through diplomatic channels in Warsaw, Poland. Kissinger frequently worked the back channels of diplomacy, informally contacting representatives and talking with them. Kissinger and his small staff controlled

the foreign policy maneuverings in a secretive, closely held style, without other civil servants bothering them.

Kissinger urged the Ambassador to Poland, Walter Stoessel, to establish some contacts first, but Stoessel declined because it was unorthodox and in a sense, dangerous. Kissinger brought him back to Washington and took him into the Oval Office. The president said to Ambassador Stoessel, “You know, the ~next time you’re at a social gathering in Warsaw if the Chinese ambassador, your counterpart, is here, I would suggest you walk up and say hello to him.” Saying hello was not that simple; no one in the U.S. embassy had any idea what the Chinese ambassador looked like.

A fashion show at the Yugoslavian Embassy in Warsaw provided the social setting Nixon had suggested. When the show ended, American officials spotted the Chinese delegation. The Americans ran after them, shouting in Polish, “We are from the American Embassy:· The U.S. ambassador panted, “I saw President Nixon in

Washington. He wants to establish relations with China.”

Back in Washington, the State Department raised concerns about the damaging effect the initiative could have on America’s allies. Nixon’s response was to cut the State Department out. The president and his national security advisor would pursue China or their own.

Pakistan was friendly with both the U.S. and China. Its president, Yahya Khan, had dinner with President Nixon in October 1970, and with the Chinese premier, Zhou En Lai, a month later. He told Zhou that Pakistan was willing to be America’s secret channel to China. Yahya Khan told the premier he had a message from President Nixon. He wanted to send an American emissary to China. Nixon wanted America and China to become friends. Premier Zhou said, “I’ll consider it-and reply later.” Nixon was

forced to wait, while Chairman Mao prepared the way for change.

Ping-Pong Diplomacy

Mao knew China’s main threat was the Soviet Union. That was why he wanted to break the ice with the United States, because otherwise, he said, China would face enemies on both fronts. Mao had another motivation: Taiwan. Traditionally a part of China, the island was ruled by Mao’s old enemy, Chiang Kai Shek. Mao wanted Taiwan back. He

thought that a new relationship with Nixon could help. There were risks, however. America was at war with North Vietnam, China’s ally. And China’s hardliners- including Mao’s own wife-would certainly resist any normalization with the West.

Mao moved forward covertly. In April 1971, he sent an invitation to the U.S. table tennis team, then in Japan, to tour China. Mao’s offer said simply, “The regards of the Chinese people to the American people.” The tour showed the new, friendly face of China to the world. Vice President Spiro Agnew criticized the trip, calling it a “propaganda triumph” for the Chinese. Agnew, who had no idea of Nixon’s secret plan, was promptly told to keep quiet.”

Kissinger Tests The Waters

After six months of waiting, a top-secret message from Mao to Nixon came through, conveying Chairman Mao’s personal invitation to President Nixon to visit China. But first, an American envoy would be dispatched to Beijing to make the delicate arrangements. Kissinger was the only choice. On July 1, he embarked on an elaborately deceptive journey, a public tour of Asia. When Kissinger and his entourage arrived in Pakistan, President Yahya Khan put the secret plan, code-named Marco Polo, into action. Kissinger feigned illness at dinner and excused himself. While a Kissinger stand-in feigned recuperation in his place, Kissinger was driven to the airfield in the middle of the night. The world’s press, the U.S. Embassy staff, and all the members of Nixon’s cabinet, were kept in the dark.

Shocked to see four Chinese in Mao jackets in the plane, Kissinger’s body guard thought they were being kidnapped! While in flight at 4 a.m., Kissinger realized he had not brought another shirt. The national security advisor had only 48 hours to lay the groundwork for Nixon’s visit. He was about to greet the prime minister of a government America did not officially recognize- in a borrowed shirt several sizes too large. The meeting was successful, after initial nervous assurances by Kissinger that America had no designs on Taiwan. But when asked for assistance to help extricate America from Vietnam, the Chinese premier adamantly stated, “No deal! U.S. troops must go. You must just get out. Let the Vietnamese solve their own problems.”

Nixon Goes To China

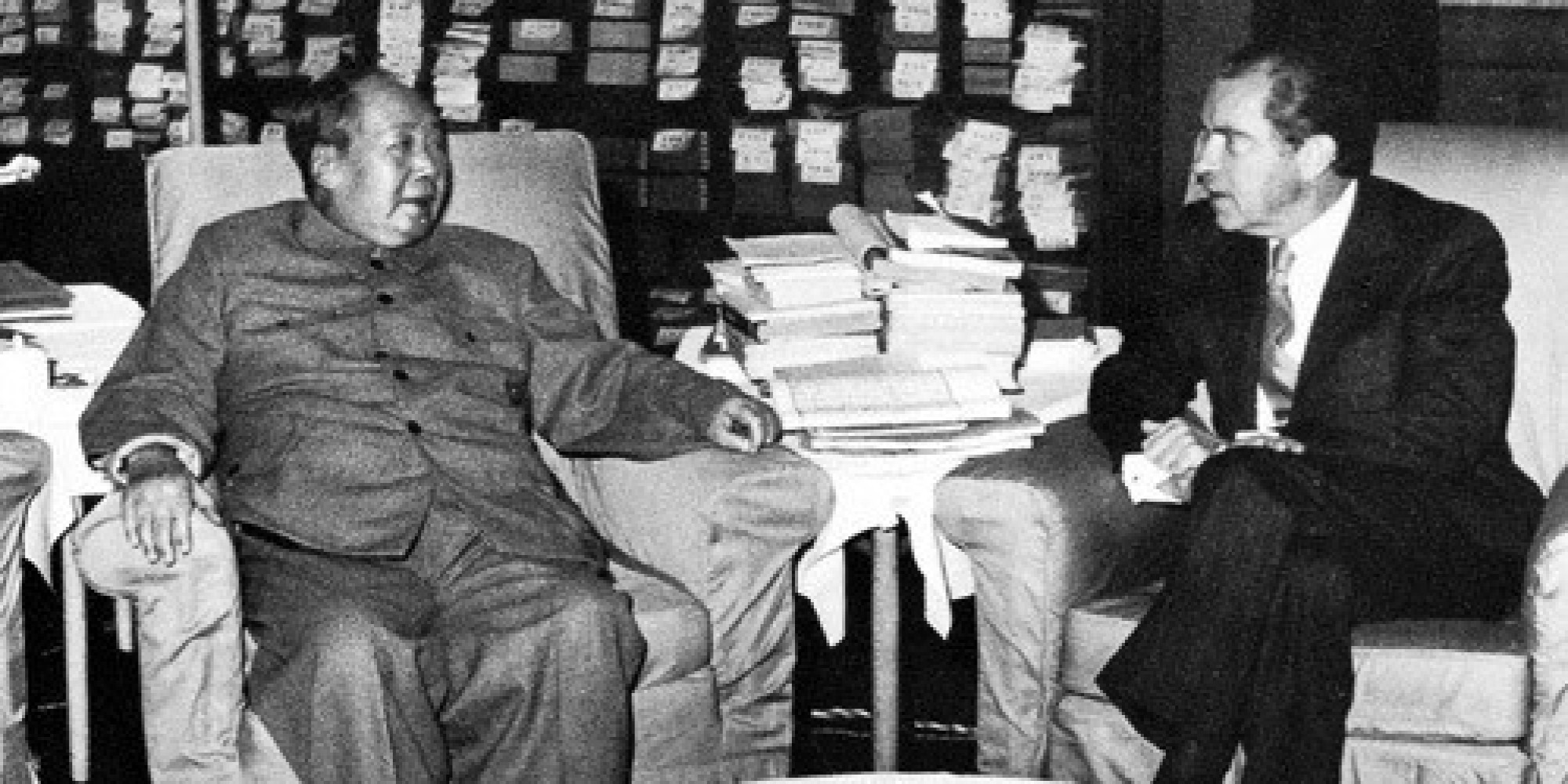

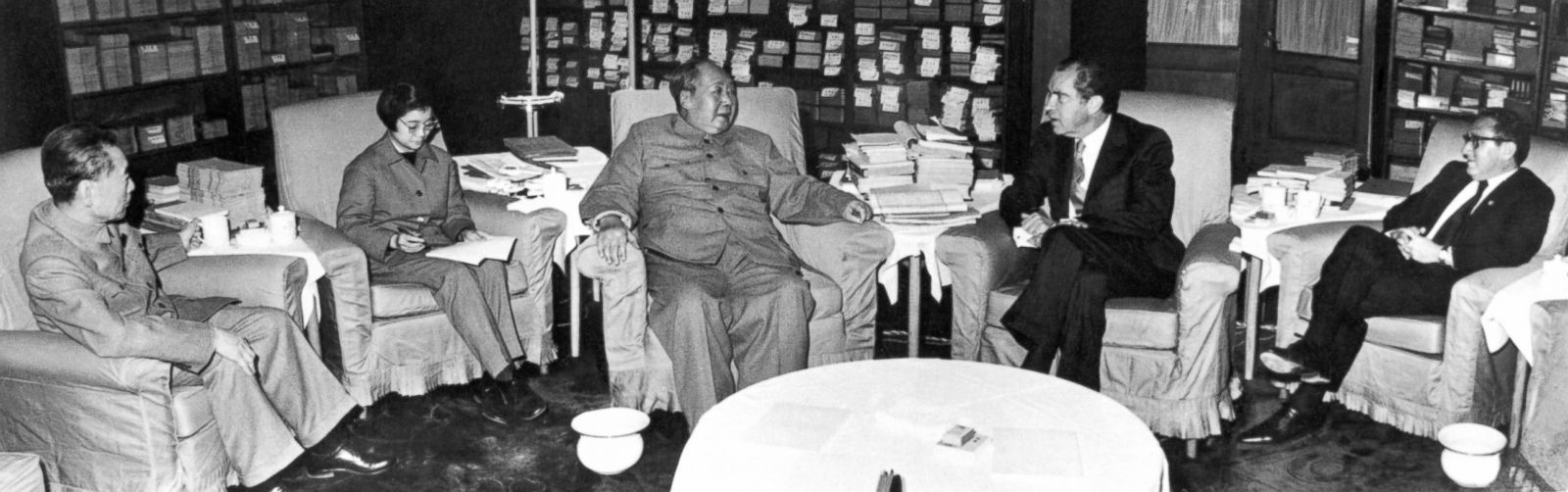

When Nixon’s trip was announced, politicos and bureaucrats around the world were indeed shocked. The status quo of world politics had just been shaken up. On February 17, 1972, Richard Nixon set out on his historic trip to China. Two years of effort had led to the moment, yet no one knew if the Chinese were prepared to agree to anything. The

script had yet to be written. Nixon did not even know if there would be a meeting with Chairman Mao. ”We were embarking,” Nixon, remembered, “On a voyage of philosophical discovery as uncertain, and in some ways as perilous, as the voyages of geographical discovery of an earlier time.”

On Monday, February 21, 1972, President Richard M. Nixon arrived in Beijing, China, in the Spirit of ’76, the presidential jet. He was greeted only by occupants of an unmarked vehicle and no crowd. Nixon was informed that he would be at his first meeting with Premier Zhou En Lai in just three hours. It was customary at the time to quickly get important figures to their meetings so that nothing could interfere with diplomatic proceedings. President Nixon met with his hosts at the Great Hall of the People, where the talks would range from 40 minutes to four hours.

During the meetings, they tried to establish goals for what the two nations would like to accomplish together. They established clear understandings on where they stood with regard to the territorial acquisitions of mainland China, and their mutual wariness of the Soviet threat. The meetings were regarded then, and today, as a historic rapprochement between the U.S. and China. Step by delicate step, the events led up to what Nixon called “The week that changed the world.”

Were the description above not further illuminated, the enlightened initiative, boldness and courage displayed by two of the most important world leaders of the 20th century could not be appreciated. The story of Nixon’s groundbreaking visit to China was fraught with secrecy, intrigue and deft maneuvering by both leaders. Under the shroud of Cold War politics, President Richard M. Nixon, ardent Cold War warrior, secretly initiated the beginning of the end of the Cold War, but he couldn’t have done it without the cooperation of communist Chinese leaders Mao Zedong and Zhou En Lai.

The Taiwan Issue

Nixon’s desire to keep the on-going talks with the Chinese secret extended even to his own secretary of state, William Rogers. Behind closed doors, the two countries were crafting a joint communique that would both recognize Mao’s claim to Taiwan and honor the American commitment to defend Taiwan. The wording was carefully worked out in a series of meetings: The document stated that, “All Chinese on both sides of the Taiwan Strait believe there is one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.” The president approved it in the middle of the night. The Chinese Politburo approved it for the Chinese side. Only on the flight from Beijing to their next stop, Hangzhou, were members of the State Department shown the communique. It did not address who should govern that “One China.” Furthermore, treaties with some, but not all Asian nations, were mentioned. That caused a great disturbance between the State Department camp and the White House camp. Nixon was furious. Zhou En Lai decided to act. He realized that the president had played very fast and loose with the State Department. He said to Rogers, “It’s so important: Our two countries have come together and this is the major thing, and we hope that Mr. Rogers would understand that, and would fully give the support.” Rogers then agreed to support the communique. The communique ended up with all references to mutual defense treaties deleted, and that was acceptable to the Chinese.

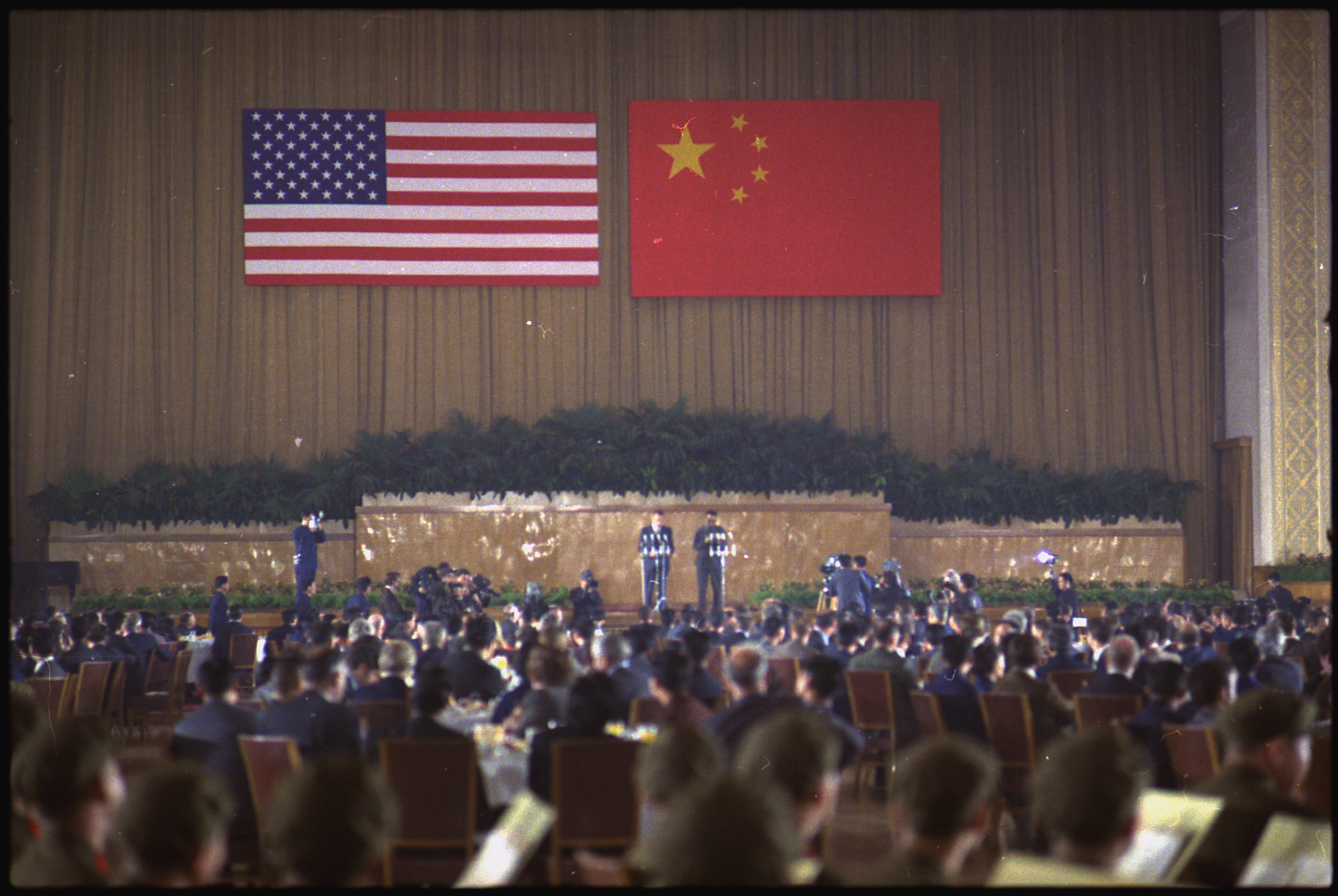

Triumph

At the final banquet , a triumphant and tipsy Nixon exulted, “We have been here a week. This was the week that changed the world!”